Biometric ID Cost-Benefit Calculator

For millions of refugees around the world, the biggest barrier to financial survival isn’t lack of money-it’s lack of proof that they exist. No passport. No birth certificate. No government-issued ID. Without any of these, banks won’t open an account. Mobile money services won’t register them. Even basic things like sending money home or buying a phone SIM card become impossible. That’s where biometric IDs come in. These systems use fingerprints, iris scans, or facial recognition to confirm who someone is-no paper needed. And they’re changing how refugees access finance, fast.

How Biometric IDs Solve the Refugee Identity Crisis

Before biometrics, refugee registration relied on paper cards, handwritten lists, and memory. These systems failed often. Cards got lost. Names got misspelled. People got registered twice-or not at all. In 2015, UNHCR launched its first biometric identity system to fix this. Today, it’s active in over 90 countries. The system links a person’s unique biological traits-like their fingerprint or iris pattern-to a digital record. That record stays safe, even if the person moves camps or countries. The results are clear. In Ethiopia’s Fayda ID system, which now covers nearly 1 million refugees, verification that once took days now takes under 30 seconds. Before biometrics, less than 1% of refugees had access to formal financial services. After implementation, that jumped to 25%. In Pakistan, the NADRA system linked to 45 banks and mobile money providers helped 68% of refugee women open their own accounts for the first time. One woman told researchers, “Before, my husband controlled all the money. Now I have my own account and can work.” This isn’t just about convenience. It’s about dignity. When you can open a bank account, you can save. You can pay for school. You can start a small business. You’re no longer dependent on aid alone. Biometric IDs turn refugees from invisible people into verified customers of the financial system.The Technology Behind the Identity

Most refugee biometric systems use a mix of fingerprint and facial recognition. Some, like Ethiopia’s Fayda ID, also include iris scans. These aren’t stored as photos. Instead, the system converts the scan into a mathematical code-a template-that can’t be reversed into an image. This is key for privacy. Raw biometric data isn’t kept anywhere. Only the code is stored, encrypted with AES-256, the same standard banks use for online transactions. The hardware is simple: mobile tablets with built-in scanners. Field workers go into camps, enroll people, and upload data to a central server. The server connects to banks, mobile money apps, and aid distribution systems. When a refugee wants to withdraw cash or pay for goods, they place their finger on the scanner. The system matches the template in under a second. No card. No PIN. Just their body. The accuracy is high-99.8% according to UNHCR’s own testing. That means fewer errors, fewer disputes, and less fraud. In cash-based aid programs, fraud rates were 8-12%. With biometric verification, that dropped below 0.5%. That’s not just a win for efficiency. It’s a win for trust. Aid organizations can prove their money is reaching the right people. Governments can track who’s getting what. And refugees? They get reliable access without begging for proof.Privacy Risks You Can’t Ignore

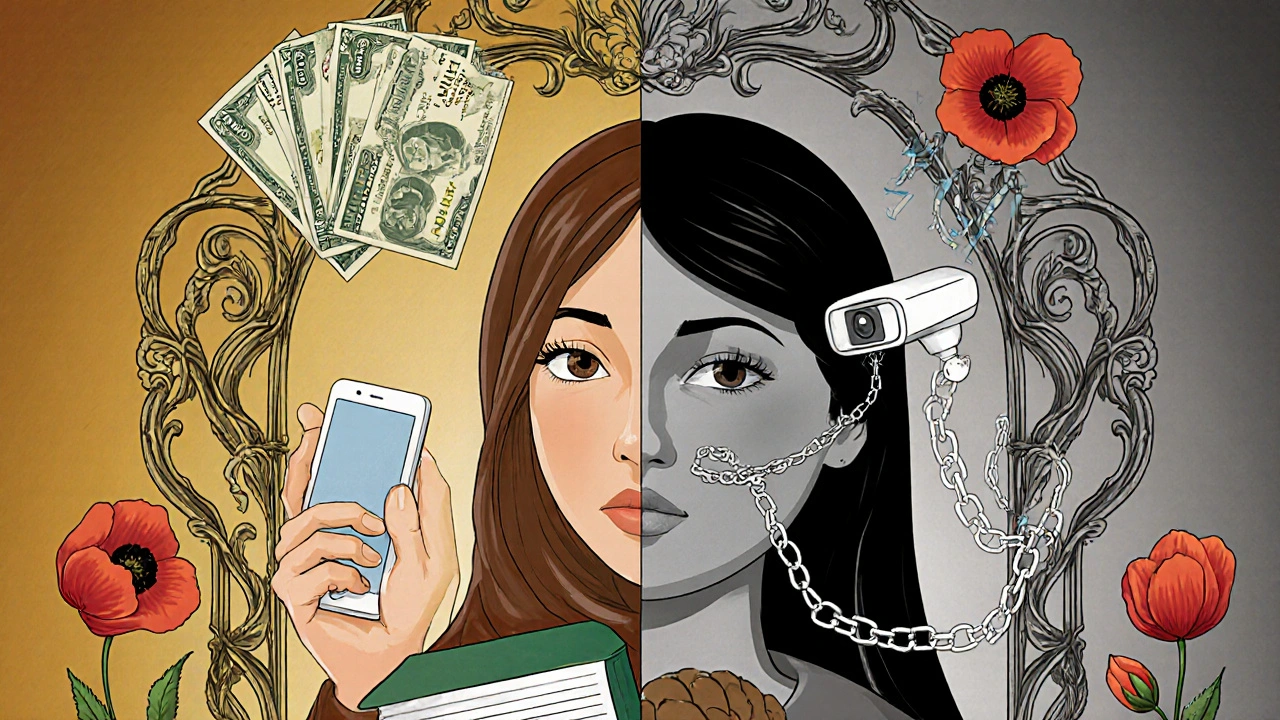

But here’s the flip side: every time your fingerprint is scanned, it leaves a digital trail. And that trail can be tracked, hacked, or misused. In 2024, the Electronic Frontier Foundation documented 14 cases where refugee biometric data was accessed without consent-mostly by host country authorities. In one case, a government used fingerprint records to identify and deport people who had applied for asylum. In another, data from a refugee ID system was sold to a private company for marketing purposes. The problem isn’t the technology. It’s the lack of rules. According to the Brookings Institution, 57% of host countries have no specific laws protecting refugee biometric data. Even when data protection laws exist, they rarely cover displaced populations. Refugees can’t vote. They can’t sue. They can’t demand transparency. And most don’t understand what happens to their data after enrollment. A 2024 survey in India found that 82% of refugees worried about misuse of their biometric information. Yet, 76% still preferred digital IDs over paper because paper could be stolen or destroyed. That’s the cruel trade-off: more access, more risk. Dr. Sarah Collinson of the Overseas Development Institute calls it a “double-edged sword.” Biometrics give refugees financial power-but also make them vulnerable to surveillance. “Once your biometrics are in a database,” she says, “you’re no longer anonymous. You’re a record. And records can be used against you.”

Infrastructure Gaps and Real-World Failures

Biometric systems look perfect on paper. But in practice, they break. In many refugee camps, electricity is unreliable. Internet connections are spotty. Solar panels don’t always charge. Tablets get dropped. Scanners stop working. In 22% of remote camps, biometric verification fails because of technical issues, according to UNHCR’s 2024 assessment. One refugee on Reddit wrote: “The biometric scanners at our camp broke 3 months ago and nobody fixed them. We’re stuck without ID while locals get services.” And not everyone’s fingers work for scanning. People who do manual labor-carrying water, building shelters, farming-often have worn or damaged fingerprints. A 2023 IRC survey found that 37% of working-age refugees had fingerprints too damaged for reliable scans. That means a large portion of the population is left out, not because they’re fraudulent, but because their hands tell a different story. Even when the tech works, the system doesn’t always include them. Only 44% of refugee ID programs provide enrollment instructions in more than three languages. Many refugees don’t know what they’re agreeing to. They’re told, “Put your finger here,” but not, “This will be stored forever. No one can delete it.”Costs, Benefits, and the Road Ahead

Implementing biometric IDs isn’t cheap. It costs about $8.50 per person to set up-nearly three times more than mobile-based ID systems. But the long-term savings are huge. Organizations save $15 per refugee annually by cutting down on fraud, duplicate registrations, and manual paperwork. In Ethiopia, integrating refugees into the national ID system reduced administrative costs by 20%. The market is growing fast. The global humanitarian biometric ID sector hit $287 million in 2024 and is growing at 14.3% a year. More than 60% of new refugee ID programs now use biometrics-up from 42% just five years ago. Major banks in refugee-hosting countries have jumped in too. In Q1 2025, 73% of large banks allowed refugees to open accounts using biometric verification, up from 39% in 2022. The next step? Credit. Ethiopia’s Fayda ID system just launched credit scoring in April 2025. Now, refugees with consistent transaction histories can get small loans to start businesses. That’s huge. It’s not just about access-it’s about inclusion. Pilots are also testing blockchain-based verification, where data is stored across multiple servers instead of one central database. This could reduce the risk of a single breach. But it’s still early. And without strong legal protections, even decentralized systems can be misused.

What Refugees Really Think

Real people aren’t just statistics. They’re the ones living with this tech every day. One refugee in Ethiopia, who goes by “AddisAbabaRefugee2020” on Reddit, says: “Before getting my Fayda ID, I couldn’t open a bank account or get a SIM card. Now I have a mobile money account and sent $50 to my family last week-but I worry about who can access my fingerprint data.” Another, a woman in Pakistan, said: “I didn’t know I could have my own money. Now I save for my daughter’s school. But I still don’t know if the government can see my transactions.” These voices aren’t outliers. In 63% of refugee settlements, people say they’d prefer to use biometric IDs-but only if they could control who sees their data. They want transparency. They want the right to delete their records. They want to know what happens if they return home. The UNHCR’s 2025 update to its Data Protection Policy now requires host countries to prove that the benefits of biometric IDs outweigh the privacy risks. That’s a start. But enforcement? That’s still weak.Final Thoughts: Access Without Exploitation

Biometric IDs for refugees aren’t a magic fix. But they’re the best tool we have right now to give displaced people real financial power. They reduce fraud. They cut costs. They connect people to services they’ve been denied for years. But technology alone won’t protect them. Without strong data laws, independent oversight, and refugee-led input, these systems risk becoming tools of control-not liberation. The goal shouldn’t be to track refugees. It should be to empower them. The future of refugee finance depends on one question: Can we build systems that are as secure for privacy as they are for access? If the answer is yes, then biometrics can be a bridge-not a cage.How do biometric IDs help refugees access banking services?

Biometric IDs use fingerprints, iris scans, or facial recognition to verify a person’s identity without needing physical documents. Since most refugees lack passports or birth certificates, banks and mobile money providers can’t verify them traditionally. With biometrics, they can instantly confirm who someone is, allowing them to open bank accounts, receive aid payments, and use mobile wallets-something nearly impossible before these systems were introduced.

Are biometric IDs safe for refugees’ privacy?

It depends. The technology itself is secure-biometric templates are encrypted and stored as unreadable codes, not images. But the real risk lies in how the data is managed. In 57% of host countries, there are no specific laws protecting refugee biometric data. This leaves refugees vulnerable to misuse by governments, corporations, or hackers. There have been documented cases of biometric data being used for deportation or surveillance, making privacy a major concern despite the technical safeguards.

What happens if a refugee’s fingerprint is damaged?

Fingerprint damage from manual labor-like carrying heavy loads or working with rough materials-affects about 37% of working-age refugees, according to the International Rescue Committee. When this happens, systems may fail to recognize them. Some programs use backup methods like facial recognition or iris scans, but not all do. In many camps, there’s no fallback, leaving these individuals locked out of services they need.

How much does it cost to implement biometric ID systems for refugees?

The average cost to enroll one refugee in a biometric system is $8.50, according to World Bank analyses. This covers hardware, training, and infrastructure. That’s more than double the cost of mobile-based ID systems ($3.20 per person). But biometric systems save $15 per refugee annually by reducing fraud, duplicate registrations, and administrative work. The long-term financial return makes them cost-effective, even if the upfront cost is higher.

Which countries are leading in refugee biometric ID adoption?

Ethiopia leads with its Fayda ID system, which integrates nearly 1 million refugees into the national ID framework and connects to 17 financial institutions. Pakistan’s NADRA system also includes refugees and links to 45 banks and mobile money providers. India extended its Aadhaar system to refugees in 2023. Jordan and Uganda have implemented UNHCR-backed biometric programs, and the World Bank is now scaling Ethiopia’s model to eight more countries through 2027.

Can refugees delete their biometric data if they want to?

In almost all cases, no. Once enrolled, biometric data is stored indefinitely in centralized databases. Even if a refugee returns home or gains citizenship, their data usually remains. There are no global standards allowing refugees to request deletion. The UNHCR’s 2025 policy now requires host countries to assess privacy risks before launching systems, but it doesn’t guarantee data removal rights. This is one of the biggest unresolved ethical issues in refugee digital identity.

Julia Czinna

It’s wild how something as simple as a fingerprint can unlock entire lifetimes of dignity. I’ve worked with refugee communities in Arizona, and the relief on people’s faces when they finally get to open a bank account? Unforgettable. But the lack of data rights is terrifying. No one should have to trade their privacy just to survive. We need binding international standards-not just ‘good intentions’ from NGOs.